Many readers of these Communiquées will remember the late, great ESTAR(SER) scholar Gregg C. Toomey (1958-2018), whose unparalleled review essay, “ESTAR(SER) and the W- Cache: The State of the Discussion” (originally published in the Proceedings, New Series v, Vol. 3 [2013]: 1–16), was recently reprinted, as Chapter 3, in the “Best of the Proceedings” volume, In Search of the Third Bird (London: Strange Attractor, 2021). Toomey was, of course, something of a “character,” and, even by his own account, a persistent thorn in the side of the administration at Ball State. He had a reputation as a practical joker, but at times it could be difficult to tell if he was joking. An unfinished short manuscript by Toomey, recently come to light, has left a number of us uncertain as to his intentions in this regard. We offer a précis of the problem here, in case anyone has any ideas.

The term “bird” is surely “polysemous,” in that we have no shortage of meanings (hugely diverse!) that have been associated with the word. Used as a verb and a noun, and deployed in a host of settings (including many slangs), the term can sometimes seem too slippery for reliable communication. Toomey, of course, taught in the Communications department at Ball State, and had a longstanding interest in American popular argots. A folder of notes found in his Nachlass reveals that he collected a host of sources bearing on the stemma of the expression “The Bird is the Word” – a jingle best remembered in connection with the 1963 hit by the landlocked midwestern “surfing” band, the Trashmen, “Surfin’ Bird,” in which, amidst a bass-line warble of indecipherable phonemes, the agitated lead vocalist continuously chants “The Bird, the Bird, the Bird is the Word.” The lyrics can be reconstructed as follows:

A-well-a everybody’s heard about the bird

B-b-b-bird, b-birdd’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, bird is the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, well-a bird is the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, well-a bird is the word

A-well, a bird, bird, b-bird is the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, well-a bird is the word

A-well, a bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well-a don’t you know about the bird?

Well, everybody knows that the bird is the word

A-well-a-bird, bird, b-bird’s the word, a-well-a

A-well-a everybody’s heard about the bird

Bird, bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well, a bird, bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well-a don’t you know about the bird?

Well, everybody’s talking about the bird!

A-well-a bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well-a bird, surfing bird, brr, brr, ah, ah

Ah, bap-a-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pap

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-ma-ma, ma-ma-mow

Ma-ma-ma-ma, ma-ma-mow

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow

A-well-a don’t you know about the bird?

Well, everybody knows that the bird is the word

A-well, a bird, bird, b-bird’s the word

A-well-a mow, mow, pa-pa, ma-ma-mow, pa-pa

Ma-ma-mow, ma-ma, mow, pa-pa

Did Toomey actually believe that this song spoke to the history of the Order of the Third Bird? It seems unlikely. There are many reasons to doubt the connection. Minneapolis native Steve Wahrer, the drummer and lead vocalist for the Trashmen (who conjured the hit), is not otherwise known to have associated with the Avis Tertia, or to have shown any particular interest in durational exercises of immersive attention of a “Birdish” character. Toomey may have collected the related sources, then, as part of a gag, or in connection with a piece of nonce-scholarship with which he may have intended to amuse a few colleagues.

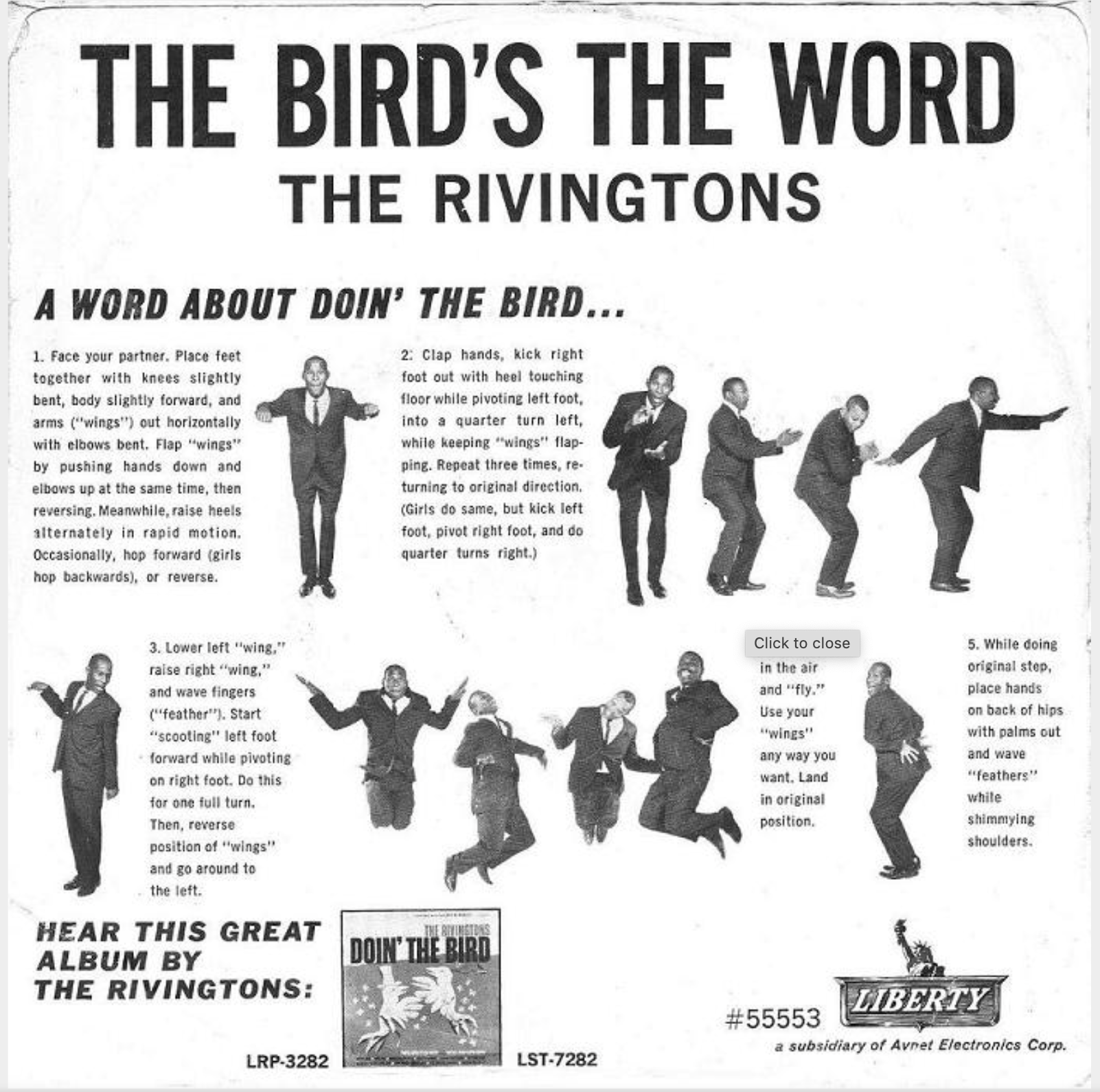

But there is evidence that Toomey may have gotten increasingly seduced by the intricacies of the story he gradually uncovered. After all, Wahrer and the Trashmen ultimately had to cede credit for “Surfin’ Bird,” after legal proceedings revealed what many insider-aficionados already knew: the song was a satura (at best) or, less charitably, a total rip-off, in that the lyrics and the tune had been cobbled together, without acknowledgement, from the work of the African-American R&B band The Rivingtons, whose “The Bird’s the Word” had established the gnomic refrain, and whose “Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow” set the canonical bass-line. Both releases predated “Surfin’ Bird” (the latter in 1962; the former in 1963, but in advance of the Trashmen’s vinyl). A settlement was reached. The Rivingtons themselves followed up on the success of “Surfin’ Bird” (which reached #4 on the Billboard top 40) by producing a new song, “Mama-Oom-Mow-Mow” which (like the work of their plagiarists) integrated the bass-line of “Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow” with the lyrical elements of “The Bird’s the Word.” Released on a new LP entitled “Doin’ the Bird,” the song failed to chart.

The “Bird” in this context was, of course, a dance, the moves of which are demonstrated here, on the back of a subsequent Rivington’s album:

There is a good deal of material in Toomey’s final writings suggesting that he came to suspect that there was, in fact, a genealogical link tying the somatics and kinetics of the “Bird” to “Birdish” practices of ludic aesthesis. But did he, really? Anyone having further archival information or other insights on this matter is invited to pass correspondence to the Secretary.