A correspondent member of the Order of the Third Bird, Crake (Crex crex) has passed to us, via an unnamed Informant and the Secretary Locotenant of the Order, “the story of a most unusual Negation,” which we reproduce here with its accompanying images.

“In the Old City of Jerusalem there are a number of historical buildings and monuments belonging to a waqf associated with a distinguished Arab family that figures in Jerusalem history dating back to the Crusades. Some of the buildings are located in areas accessible only to Muslims, but a special invitation from the archivist of the waqf‘s distinguished manuscript collection secured for my informant the right to march right past the Israeli police, down an alleyway, and up a flight of stairs, where along with some fellow Birds he carried out an Action among the shelves of a small but bountiful library of books, as the ululations of a call to prayer from the nearby Omar Mosque echoed outside.”

The informant cannot be certain which item in the room is the object of the Action, and during the Negation has recourse, in somewhat unorthodox fashion, to “the divinatory art”:

“… the action took place in a library, one that was focused on, but not limited to, the history of the city that hosts it. Of course one of the most basic forms of divination consists in opening a book at random and seeing what the book has to say there in that spot. My informant tells me that he determined to take down two books, chosen from opposite ends of the library, and that the choice would be made simply by looking at the shelves and seeing which books ‘called him to them’. The books he ended up with by this technique were, first of all, Al-Ghazali’s 11th-century treatise, Tahāfut al-Falāsifa (The Incoherence of the Philosophers), and, second of all, Leroy J. Pinn’s 1948 wood-carving manual, Let’s Whittle.

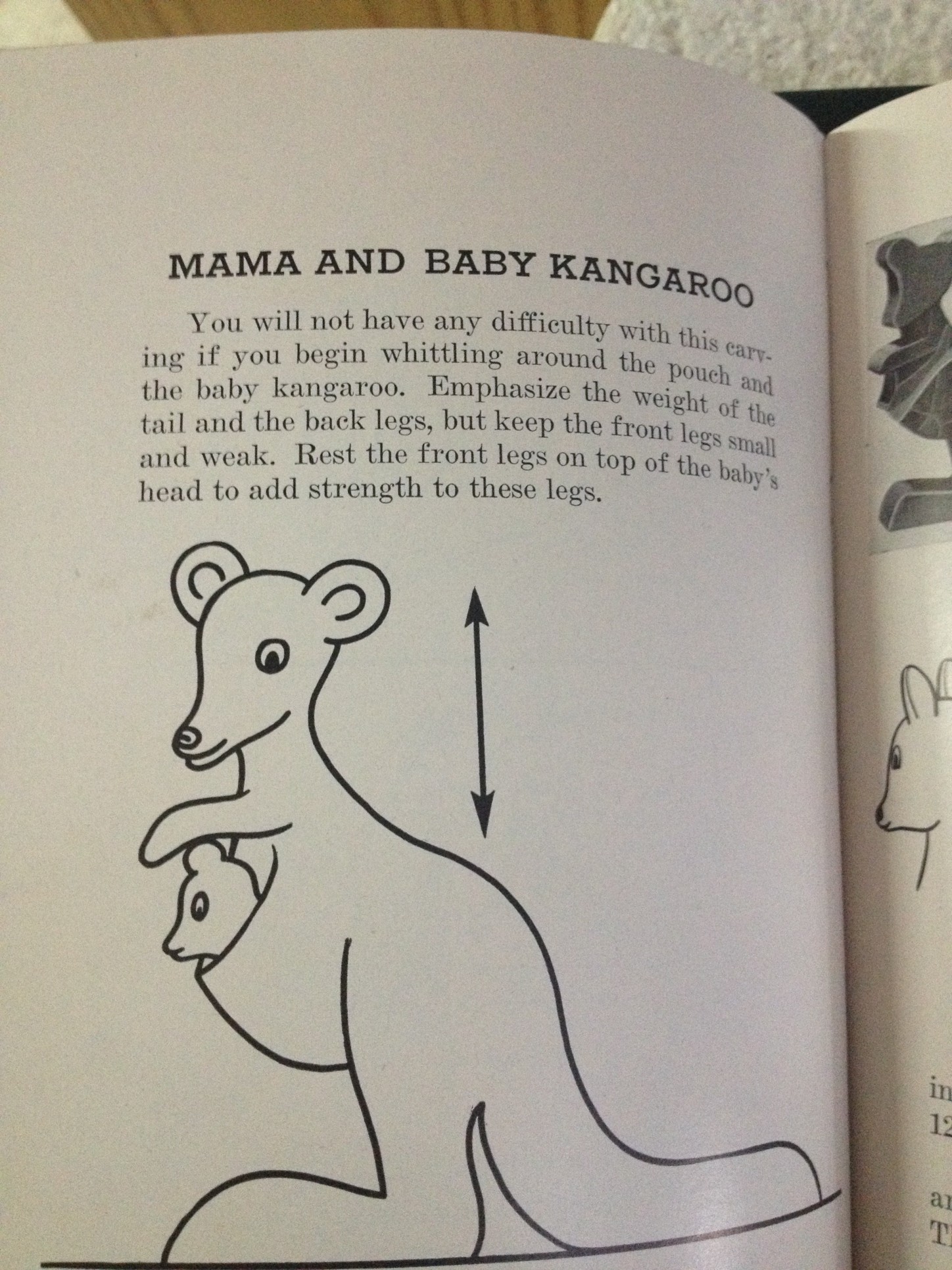

My informant found it fitting to look first into the book on whittling. He opened it to a page that explains how to carve a mother kangaroo with a baby in her pouch. “You will not have any trouble with this carving,” Pynn explains, “if you begin whittling around the pouch and the baby kangaroo.” The whittler is instructed to make the back legs big and strong, and the front legs, which he is not willing to call ‘arms’, small and weak.”

“He next turned to The Incoherence, whose author had been a Persian Sufi and mystic dissatisfied with the attempts made by predecessors such as ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Al-Farabi at exhaustive knowledge of the divine by means of philosophical argumentation. Within a few decades of its publication in 1095, Al-Ghazali’s treatise would be mocked by ibn Rushd (Averroës) in what is perhaps the most cleverly titled work in the history of philosophy: The Incoherence of the Incoherence.“

“As in any mystical work, there is a certain apophatic element in Al-Ghazali’s approach, though The Incoherence is far from being a simple defense of the via negativa. On the page to which my informant opened, in the middle of Section 56, we find Al-Ghazali arguing against the Aristotelian view that the Divine has no awareness of the world. Since God is the creator of the world, and we have knowledge of God, the author argues, if God had no knowledge of us then we would be nobler than God in respect of knowledge. But this is absurd. Therefore, &c.”

This leads to further reflections. A creator, for example:

“…must necessarily know the thing created. But within this broad constraint there are many ways of knowing and creating. There is, first of all, the knowledge of the Whittler, which has served for many as the model of artistic creation in general, as when it is said that the sculptor does not make a statue, so much as he frees it from the surrounding stone in view of some idea that he has of what the statue is to look like: in view, in other words, of some object of knowledge. There is, next, the Progenitor, as for example the mama kangaroo, who holds her baby within her pouch, is responsible for its helpless marsupial being and knows it as intimately as any creature ever knew another, even to the extent that one could hardly call it another, but who never sculpted or constructed it as an artificer with a blueprint. No, instead it just came out of her.”

“Where then do things stand with the third sort of creation, that of God in relation to the world? How does God create the world, such that he at once knows it to be his creation? Does he whittle it? Or does it just come out of him? Or is there some other mode of creation, some hypostasis or overflowing or parthenogenesis, or some other process still, unthinkable by the human mind?

And why, finally, my informant thought as the phase of Negation approached its end in the library of the waqf in the Muslim Quarter of the Old City, should these exercises of Attention of ours be limited to the objects of Art: the objects, he said to me, that always come forth through some form or other of Whittling, a via negativa if there ever was one, and never any of the more exalted forms of Creation?”