We learn, in a recent message from the Secretary Locotenant of the Order of the Third Bird, that groups of practitioners associated with the Order were indeed present in Bologna and Florence near the end of the 16th century. However, we also learn that the correspondence purportedly exchanged between an Order member and the ecclesiastic Gabriele Paleotti, while the latter was working on his Discorso intorno alle imagine sacre et profane, is almost certainly a late 19th century forgery. In this apocryphal correspondence, Paleotti and the unnamed Bird are engaged, remarkably enough, in discussion of “apocryphal” images – a discussion from which Paleotti ostensibly quotes in his 1582 magnum opus. The Bird remarks that like apocrypha, Order members who are deeply habituated to the practice and enmeshed in the Order’s workings and doings must all the more lead “an occult and unremarked existence.” As he/she explains: “Power abhors a vacuum. Even in a collective that eschews the obvious manifestations of power, it often circulates for brief periods around certain figures. But it is the responsibility of these latter, if they are honest, scrupulous, and spry, to elude it.”

Monthly Archives: October 2014

Temporary Legendary Psychasthenia Can Occur…

A provocative quotation from the great sur-rationalist Roger Caillois, in a footnote to his 1935 essay “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia”:

Pour ma part, d’ailleurs, si l’on veut réduire l’instinct esthétique à une tendance de métamorphose en objet ou en espace, je ne m’y oppose pas.

“In any event, I myself have nothing against the attempt to reduce the aesthetic instinct to the tendency to become transformed into an object or space.”

One admires Caillois’s decision to write “tendance de métamorphose” rather than a mere “désir de métamorphose.” The absence of a qualifying “temporaire,” however, is troubling.

An Amusing Apocryphon

Certain of our readers perhaps have friends or acquaintances who suffer from a passion for contemporary kung fu films.

Our archives contain a letter from a known Paris associate of the Order to an individual – an amateur Orientalist of the fin-de-siècle, an indolent and epitomically neurasthenic contemporary of Huysmans’s Des Esseintes – who had amassed an enormous library devoted to the Chinese and Japanese martial arts, and to any work glorifying, mystifying, or otherwise embellishing them. This individual, J.-P. M. de Fohat, was a willfully credulous type, and probably delighted by the fanciful fiction that the contents of the letter most likely represent. The extent of de Fohat’s acquaintance with the Order is not presently known to us, though he was evidently familiar with certain of its terminologies. However, we can paraphrase the letter’s contents – whose interest derives in part from dubious details about the secretarial role in the Order – as follows:

In mid-eighteenth-century Japan, the Order in that region possessed a fairly competent military wing, for the stated purpose of self-defense. The letter author indicates the presence, in that context, of a chōjimujikan (鳥寺務次官)– coining a hybrid term in which the characters ordinarily used to denote an under- or vice-secretary in a modern bureaucracy are replaced by the homophonic characters denoting a Buddhist temple administrator (the import of the first character, of course, will not escape our readers). It was this “bird temple secretary,” to attempt a translation, who proposed that a certain cell of the Order in the Kantō area carry out an action on a battlefield, while a battle was taking place. It is unclear whether the object of the action was a concrete thing, like armor or ensigns, or more abstract, like the patterns and vividry of the battle itself. The “secretary,” it seems, doubled as commander of the armed defenders of the group, who stood in a vacuole of relative calm as the warriors circling them fought off stray attackers. It also seems to be the case that the warriors themselves participated in the action, performing a quick and streamlined version of its standard sequence during each personal skirmish, which they believed enhanced their skill in battle.

A Message to the Editorial Committee of ESTAR(SER) from the Corresponding Secretary, Eastern Consistory

An Additional Note on Walt Whitman

John Burroughs, in his 1867 Notes on Walt Whitman as Poet and Person (section XXXI) employs three birds in his account of the necessity of encountering objects in the fullness and richness of their surroundings and histories:

It must be ever present to the true artist in his attempt to report Nature, that every object as it stands in the sequence of cause and effect has a history which involves its surroundings, and that the depth of the interest which it awakens in us is in proportion as its integrity in this respect is preserved. In Nature we are prepared for any opulence of color, or vegetation, or freak of form, or display of any kind, by the preponderance of the common, ever-present features of the earth. I never knew how beautiful a red-bird was till I saw one darting through the recesses of a shaggy old hemlock wood. In like manner the bird of the naturalist can never interest us like the thrush the farm boy heard singing in the cedars at twilight as he drove the cows to pasture, or like the swallow that flew gleefully in the air above him as he picked the stones from the early May meadow.

Why might Burroughs, close friend of Whitman, have insisted on a sequence of three birds to illustrate his point? Theories and insights are welcome.

The Third Bird and the Death of Semsem

The following is an excerpt from a folktale from the present nation of Vanuatu, about a dangerous man-eating demon named Semsem who is dispatched by some brave islanders, a mother and her sons. Semsem, pierced by spears and weakened, falls upon the ground:

The mother and the boys, fearing that he might not be dead, asked some small birds to go close to the body and see if life were really extinct. One bird touched the body of Semsem with its head and flew away in terror. This is a bird that has red feathers on the top of its head today. Another bird, more venturesome, put its head and shoulders into a wound. This is a bird that has red feathers on its head and shoulders today. A third bird went directly through the body entering at one wound and coming out by another. The bird is almost entirely red today. […] When the third bird came out of the body of Semsem the victors were certain that the giant was dead.

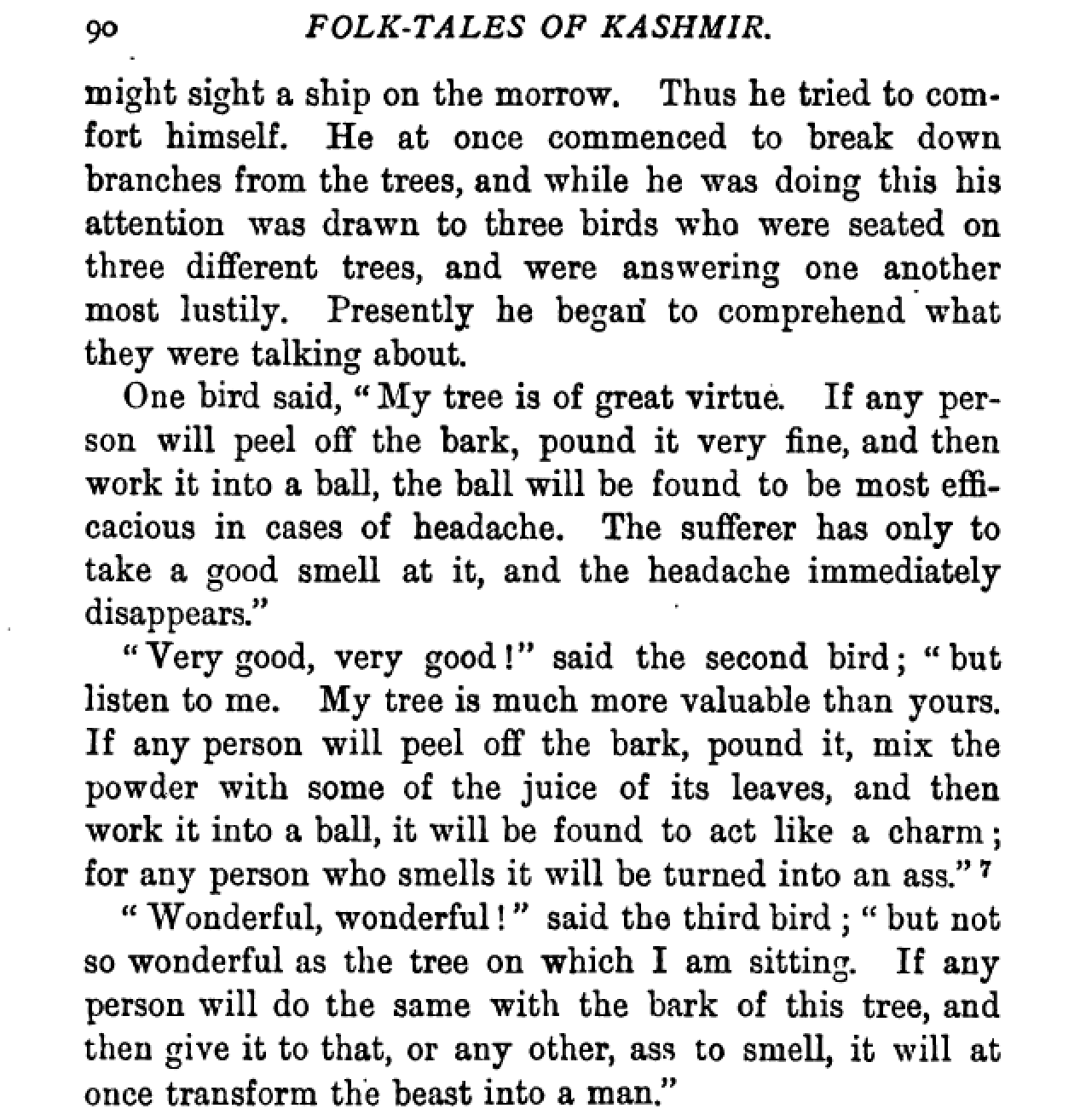

If in the Kashmiri tale below, it is the third bird’s task to transform the beast into a man, here it is the third bird’s task to confirm that the beast will not return, but only by daring to abide within, to inhabit, and finally to traverse and break free of the latter.

—Corresponding Secretary

Concerning a Kashmiri Tale…

A recent submission to Notes and Queries from a correspondent in Uttar Pradesh who is an amateur historian of the Order, and an aficionado of its ways:

“Dear Sirs and Madams: What most excellent happiness I am feeling in this day, for coming upon — MOST unexpectedly, I am telling you! — a remarkable moment for a reader who is knowledgable about the Birds and Birding and all Bird matters. To wit: In the reading of Reverend J. Hinton Knowles, F.R.G.S., M.R.A.S., et&, and more specifically FOLK TALES OF KASHMIR (London: Trübner & Co., Ludgate Hill, 1888 — picture included), I find myself lately discovering a story of tremendous and very new surprising excitement. More specifically I am now referring to the “Story of the Three Birds” that finds itself within the tale “Saiyid and Said,” at page 90 of the aforementioned Book to which I have referred (also picture being included here). If I am not very woefully in error on this occasion, this is unmistakably a story relating to the work of the Order in the KUSH region most definitely of India in older times! I am currently in need to do further researches, but the THIRD BIRD here has the POWER by his ministrations to make the human being of a non-human type of creature — and this will surely be most familiar to many who are greatly dedicated to the ORDER, as a metaphor or allegory of the humanizing effects of the Practice, it is certain.”

Both images follow — the title page, and the story in question, which comes to the Editorial Committee as a real discovery of great interest. More work is certainly needed, as it is not clear if this is an interpolation by Knowles (as a little “easter egg” for his metropolitan readers familiar with the Order), or points to residue of Central Asian Practices of greater antiquity — perhaps associated lineally with the texts discussed in the recent work on the Rülek Scrolls. More work is needed.

Screaming at the Eyes

Beautiful Birdness

There have been rumors around DeLillo for some time, of course. This is one of the lines that seems most clearly to point to his engagement with the Practice. Further work is needed…

“He watched several gulls veering and saw a hundred other gulls positioned on a slope, all facing the same way, motionless, regardful, joined in consciousness, in beautiful empty birdness, waiting for the signal to fly.” (Don DeLillo, Underworld, 186.)

A Clue against Clues

There is no property less congenial to a Bird, as we understand that fugitive spirit, than a clue: for a clue leads elsewhere. Therefore it would seem that the work of Giovanni Morelli, AKA Ivan Lermolieff—in which he proposes the value of such unregarded accidentals of the pictorial art as the shape of an ear, taken as keys to the mysteries of attribution, and a sovereign antidote to the sleights of the forgers—his work must be anathema to the Order. Some evidence has come to light, however, suggesting not only Morelli’s contact with practitioners in Germany, but that this very notion of clue might have arisen precisely as a tactic of negation. Which possibility reminds those of us concerned with the history of the Order that its traces may be discernible in sites not only of apparent neglect or indifference, but of perfect opposition.

It is hoped that the documents in question will be brought to light in due course. In the meantime, Morelli’s Die Werke italienischer Meister (1880), here in its first English translation as Italian Painters (1892), is offered to the reader’s powers of induction.