A note to the reader: The following report from the associate of the Order of the Third Bird known as Kingfisher has been translated from its original French. The letter of September 1870 quoted therein, first found in the W-Cache in January 2014, has been the subject of much controversy and excitement; it was accompanied by a number of other materials, including a fragment of a typewritten document apparently averring the letter’s authenticity, and signed “1713”; a scrap of paper on which a closely coiled spiral is drawn in black ink; and a length of purple silk rolled into a cylinder, containing a quantity of fine sand.

The First Seer: A Second Look at a Poet’s Sojourn in the Prison of Mazas

On August 29, 1870, Arthur Rimbaud slipped the surveillance of his mother and embarked upon a fugue that led him to Paris. The escapade was of short duration, since he was caught without a ticket at the Gare du Nord. At the dawn of the Third Republic and in the tense climate that preceded the Commune, the young man was carried off to the remand house at Mazas. The archives of the prison, which was known for having welcomed certain famous lodgers, permit us to know something further of the conditions of detention of the young poet. The statement of the facts of the case drawn up on August 31 contains little information, and one might easily believe that Arthur Rimbaud resided alone, in cell 42, until the fourth of September, the day of his liberation after the payment of bail by Georges Izambard, his French teacher.

However, in cross-referencing the documents that have been conserved, one perceives that a second young man occupied cell 42 before the arrival of the runaway, and remained there somewhat longer than the latter:

July 13, 1870, Paris, rue Daumesnil

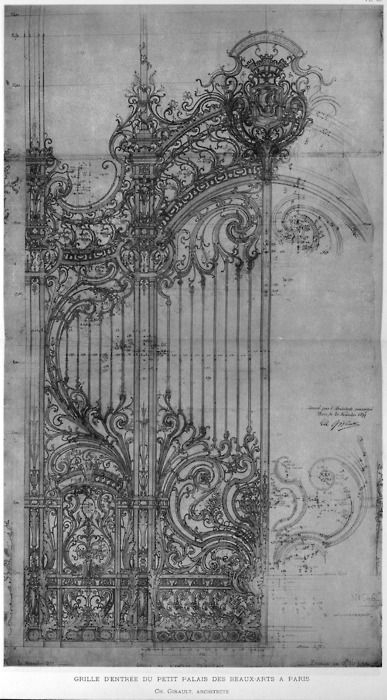

According to the declarations of the officer of the police Jean Crétut, who was off duty, and according to the testimony of Monsieurs Isidore Lelous and Jacques Gravin and in the absence of explanation by Louis Hurtière, who had kept his silence during and after his arrest at the gate of the residence of M. Lelous, before which he had remained immobile for two entire days, it was declared that the aforementioned Louis Hurtière recognized himself to be tacitly guilty of harassment of respectable women of said house and of a premeditated attempt to steal wrought iron components of the gate of the plaintiff’s domicile, which represent entwined lions. Inasmuch as the accused did not wish to remove himself from the domicile of M. Lelous, placing in danger the wife, daughters, housemaid, and above all the reputation of the household, he was placed in preventive custody. Mtr. N°3809, L.H, 13-07-1870. Cellule n°42.

No other information is accessible concerning this mysterious supposed comrade of Rimbaud’s in the cell, save a prison doctor’s report signaling “long periods of obsessional attention to objects without interest,” which give him reason to fear “the possibility of mental crises and a gradual sliding into madness,” though he had not yet noted any worsening of the prisoner’s condition.

A second, very concise report notes that “the prisoner Louis Hurtière holds himself almost immobile, occasionally moving by a step, fixing with his gaze, without any apparent signs of discomfort, varied objects including a fork, a safety pin forgotten on the corridor floor, or even a bird etched in simple curves on the wall of the cell by a previous prisoner.”

Who was Louis Hurtière? What did his curious attentional behaviors conceal? Did he have any communication with Arthur Rimbaud? What is certain is that the contemplative attitude of this inmate was enough to prompt new and careful research in the W-Cache, which contains the archives of the Order of the Third Bird; the practices of its members can be linked to what we know of the behavior of this individual locked up for having let his attention be arrested by a confection of wrought iron.

During these researches, a letter drew quite a bit of attention on the part of the W-Cache archivists. This anonymous letter was addressed to M. Georges Izambard, Arthur Rimbaud’s French teacher, and despite a lack of signature might easily be a personal letter from his student. The handwriting does not resemble that of the young boy; it is not comparable to the elegant penmanship of his first so-called “lettre du voyant.” But perhaps Rimbaud dictated this letter to a fellow student? And what if what we have here is actually the first “visionary letter,” before the well-known one written some months after its author’s release?

Paris, September 3, 1870

Cher Monsieur,

Haven’t you ever felt the need to perseverantly observe a worldly object, to the point that its lineaments seem to you renewed and remade? Have you never felt a kind of mystic obsession for what remains hidden to the eye of the ordinary? No, surely not. Your habits oblige and blind you. Do you not agree? You know my present circumstance. It causes me no suffering. It has allowed me to visit a hidden cleft in the world, a darkling fold, where I met the only true poet I have seen in this world. I did not meet him astroll in the full light of day; it is in the darkness of a cell that I find him, one from which we have already escaped. In thought, Monsieur! Thought, which you deem so powerful, but which in you is a bird that, having hurled itself endlessly at the pitiless bars of its cage, has finally ceased to struggle, and awaits its end, its wings immobile upon the straw. Your modest magician’s talents cannot produce the dark radiance of the spells I learned that day. Yes, I tell you, I have been initiated into forms of magic whose perfumes have enchanted me for ever. May you one day know such mighty effluvia as these. If you hope ever to meet a poet of the shadows, I pray you to show the same indulgence as you once did for my person and my knaveries. You have supported me; you know my defiances and follies; double, I pray you, the grace that you have shown me, and let its blind hand guide my new friend to freedom. If I do not reveal to you the ritual hours given to bring our souls to an alchemical boil, I can deliver to you the vivid result. Imagine before your eyes a safety pin – so simple, this bit of twisted iron that discreetly reflects the little light that reaches us here – then let your mind little by little unfold itself, this fine linen which I will not thus have failed to dishevel.

Flower-moire, crocodile-phosphor, subterranean-blue, eye-saw, void-tatooed, brick-cell, scarab-constellation, tooth-mirror, bosphorus-needle, skeleton-ball, crab-gloaming, Atlas-cinders, Vein-goddess, flute-ear, langour-skein, grass-silk, territory-spindle, note-alembic, caterpillar-sluice, circle-sword, iris-architect, boat-thread, comet-loop, plait-ant, mosquito-lace, victory-mien, ruin-tortoise, landscape-atom, mask-cage, horn-firefly, lantern-hollow, prism-rust, lighthouse-bird, song-pricked, chain-orange, nail-waterlilly, aileron-island, wrinkle-hatched

Numerous clues in this letter leave us to imagine that this Louis Hurtière, still unknown to us, was most likely a Bird of the Order; and it seems that his encounter with Rimbaud was exceedingly inspirational for this “thief of fire.” Knowing his amazing precociousness, it is not impossible that a part of his genius was born of an initiation into the attentional practices of the Birds, and then channeled into the creation of the poem at the end of his letter. Though some doubts remain with respect to the authenticity of the document, it is a matter only of further pursuing research toward a better understanding of the links forged between Arthur Rimbaud and Louis Hurtière.