The Case of Paulin de Barral

Modest considerations concerning a collection of stolen shoes

[A communication from ESTAR(SER) researcher Martin Pêcheur, Grenoble; Translated from the French by David De Ock]

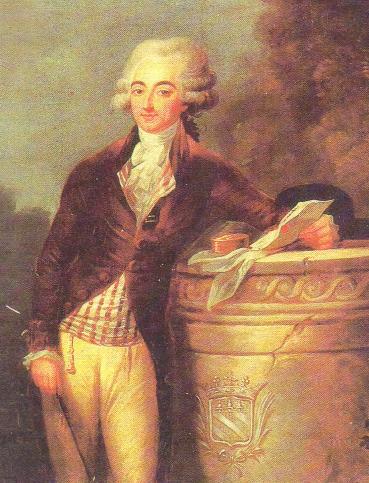

Choderlos de Laclos’ Dangerous Liaisons, the 1782 epistolary novel celebrating the louche life of the Viscount de Valmont and Madame de Merteuil, is relatively well known. What is, however, much less widely recognized is that Laclos most likely based his main character on an actual historical personage: Paulin de Barral, a noble son of the city of Allevard, located in the Gresivaudan, a valley in the Isere region of the French Alps.

This guardsman of the king, whose reputation for licentiousness has followed him over the centuries, was forcefully separated from his worldly treasure (as well as his wife), in the very year of publication of Laclos’s literary masterpiece. Dismissed from the Court, he returned to Allevard where he became director of the region’s ironworks. His fate, as well as his amorous exploits, provide a source of entertainment and humor for the citizens of Allevard to this day.

But we shall pass over these local titters in silence, and instead turn to some important historical details, which, if they can be verified, may oblige us to reconsider the life and motives of this disgraced nobleman — he who gave himself over, in his own words, “to a life of dissipation due to my own general passivity.”

Let’s start at the beginning. In 1757, the youngster Paulin was taken by his mother, the Marquise de Montferrat, to visit Voltaire in Geneva for the purpose of receiving inoculation against smallpox. These few weeks spent at “Les Delices” provided the occasion for an episode which proves, on further examination, of considerable significance to our thesis. One evening, having received his treatment from Dr. Tronchin, and while his mother discussed domestic matters with her maid (and while Voltaire himself was occupied with some manner of correspondence), young Barral seems to have exhibited a most surprising kind of behavior. When the household reassembled from its various activities, they found him alone, completely absorbed in seemingly rapturous contemplation of a single shoe, perhaps abandoned by accident in the corridor or perhaps liberated from its accustomed home by our subject himself. The group’s initial amusement soon gave way to a sense of concern when, it seems, no one was able to rouse Paulin from his trancelike fascination.

Voltaire wrote to a friend:

“The shoe in question, standing tall on its very high heel and sloping down sharply toward its pointed toe, resembled nothing so much as a small dog drawing back in fright with its forequarters scraping the floor while its haunches point toward the sky. Said shoe was decorated with a silver buckle encrusted with rhinestones, while its embroidered flanks were enhanced by the addition of well-placed seed pearls. I confess that, beyond the awkwardness of the moment for the adults present, I could easily understand how a child, victim of his own curiosity at a tender age, could be captured by such a masterpiece. I noted that in fact I myself had not always been sufficiently attentive to such magnificent works of art, essential for courtly protocol and supportive, literally and figuratively, of so many rich conversations. The episode gave me food for thought over the course of several days.”

No reference to it is to be found in subsequent writings of the illustrious philosopher, nor indeed in any correspondence of the Marquise.

It seems to have escaped the attention of critics that, despite ample documentation, echoes of this episode reverberated in the later life of Barral. Following his death, for instance, a large armoire among his belongings was found to be stuffed with a collection of shoes, apparently stolen from the court and jealously held captive by Barral himself. This strange discovery has heretofore been attributed simply to the hoarding tendencies of the deceased, but it is now time to reevaluate the episode — in light of the scandals that led to Barral’s dismissal from the court life, and in light of a deeper emergent understanding of the place of a “Birdish” sustained attention in Barral’s life.

Historians report that two grand galas took place during this period, one at the King’s Court and the other at the chateau of Cassel. Paulin de Barral was indeed a guest at both events. These same sources report that our young count “had taken it upon himself to make an inappropriate foray through the bedchambers of the fine ladies in attendance, and appropriated for himself from the personal effects of each a single shoe of great beauty,” leaving behind, in each case, an orphan now bereft of its matching companion. With the hour of the ball at hand, there was no time for the unfortunate ladies to obtain new pairs of matching shoes.

Confronted by the pressing etiquette of appearing before the Court, the ladies faced equally unattractive alternatives. Should they arrive with one bare foot hidden as well as possible under their skirts? or fail to appear at all at such an obligatory social event? Amidst general confusion, the ladies persevered in appearing as required, but without perhaps suitable attention paid to the impact of their circumstances. Teetering on a single high heel, each hobbled and limped toward the dance floor.

And thus, for the first and last time in their distinguished histories, both Courts hosted galas based on new dance forms, during which dancers hopped, skipped, and occasionally even fell — thought apparently without ever lacking in a certain grace. At the conclusion of this eminently “forgettable” event (which was, of course, indelibly remembered), the participants’ apartments were searched and Barral was found to be in possession of forty-two shoes on the first evening and thirty-six on the second. He was, needless to say, dismissed from both Courts, permanently and without redress, a banishment effected in less time than was required for the compromised ladies to reclaim their missing footwear.

It has even been asserted that, by the time that our thief was apprehended the second time, he had managed to erect a veritable pyramid of shoes rising from the floor of his own rooms, and was found in front of his bizarre construct, erect and composed, with eyes fixed on his creation. Half crazed, half enchanted, he was evidently absorbed as he had previously been as a child in blissful (if extravagant) contemplation. His titles and connections enabled him to avoid prison but not to escape exile.

In the context of historical research into the Order of the Third Bird, such events immediately suggest an opportunity of important historical revisionism.

Let us press on, therefore, with our analysis, and take a moment to pay special attention to Barral’s later (oblique) representation in literature. If Paulin de Barral did indeed inspire Choderlos de Laclos, do we find any indication of Valmont’s fascination with shoes over the course of Dangerous Liaisons? An initial textual review finds virtually no reference to “shoes” or “pumps,” and thus might discourage us from our line of inquiry. But this approach fails to capture the great number of occurrences of the word “foot” as used by Valmont throughout his correspondence, to wit:

“I will throw myself at your feet and into your arms, and I will prove to you, a million times in a million ways, that you are, that you will always be, the true queen of my heart.”

“Yes, I continued, I pledge at your feet that I must have you or I will die.”

“Only after this preliminary act of contrition do I dare place at your feet the humbling confession of my wanderings.”

“Love leads me back to your feet.”

“It is at your feet, it is in your heart that I place my suffering.”

“Like the knights of old who would place the spoils of their victories at the feet of their Ladies…”

“I was tempted over and over to invent a pretext to throw myself at your feet.”

“At a moment such as this, I feel a sense of identification with women of loose morals, and this leads me naturally to fall at your feet.”

“I contemplated for a few moments this angelic face, after gazing down from her head to her feet, I further indulged my glance in ascending back from her feet to her head.” [Translator’s note: “from head to toe” is the apt expression in English, but might confuse the issue for the reader in this case].

The links between these declarations and the episodes discussed above are not yet clear, and one could easily become engaged debating the sensual and symbolic dimensions of these passages. But there is one scene in the novel that should assist us in deepening our reading: that of the appearance of the “shoemaker” at the home of Cecile Volange. In a classic scholarly article from 1979, René Démoris analyzes this scene, focusing with great skill on the young girl’s name.

She is called “Cecile” — Caecilia. In Laclos’s work, there isn’t a moment of doubt. More than her quickly perverted innocence, it is blindness that defines the character. This characteristic is brought to light from the very first scene of the novel: Cecile mistakes a shoemaker, on his knees so that she can try on one of his creations, for a suitor! In her error, she reveals that she is already in the grasp of her figurative language, and unable to comprehend its literal meaning.

In fastening on the onomastic symbolism of her given name, we can take away from the scene that this “little blind girl” is conditioned to perceive the symbolic value of events, and to reject their more obvious, natural, and literal meanings. Perhaps the author wished, through this opening scene and through this character, to alert the reader to the most direct meaning of those scenes involving “feet.” Could we not imagine that, each time that the Viscount “throws himself at the feet” of the women in Dangerous Liaisons, he does so because of his fascination with their shoes? Are not these beautifully-shod feet simply a metonymy, a mechanism that serves as a subtle and ingenious means of obscuring Valmont’s attraction to the beauty of the shoes themselves? And what we see here, of course, is quite obviously a very direct nod to the special shoe-inclinations manifested by Paulin de Barral, Choderlos de Laclos’ Grenoblois compatriot, and Valmont’s manifest original. Surely the reader can, indeed must, escape the same blindness that afflicted Cecile in order to “see” the truth!

Anonymous engraving of the Cordonnier aux pieds de Cécile (Geneva, 1793)

Anonymous engraving of the Cordonnier aux pieds de Cécile (Geneva, 1793)

What we know for certain is that Barral’s fascination with shoes remained a constant up to the time of his death. The Baron General Thiebault, in his Memoires, mentions the presence of a “personal” collection of shoes in Barral’s possession later in life, a “cache” which is likewise referenced by Georges Salamand in his work entitled Paulin de Barral un libertin dauphinois:

“Once paralyzed, Paulin de Barral had only the glass case, in which he had arranged the shoes stolen from the ladies of the Court, as an outlet for his fantasies.”

Now, rather than seeing this case as a symbol of the fanatical dreams of a complete libertine (as do General Thiebault and Georges Salamand), we prefer to view it, given our prior insights, as reflecting the contemplative dimension of a man who was, we believe, a genuine esthete.

In fact, his reputation as “totally lacking in character” and “debauched and disheveled” is based primarily on the notorious Memoir of Madame de Barral for the purpose of obtaining physical and financial separation, 1764-1784, penned by his wife, who was describing a husband from whom she wished to separate. In his own defense, Barral would eventually assert that his wife actually composed drafts of his various love letters on his behalf! And whatever the case may be in this regard, Madame de Barral’s portrait can hardly be said to be unbiased. She is, in several places, particularly dismissive of her estranged husband’s good taste, but on this matter we have other testimony — perhaps more reliable. For instance, Alfred Bougy describes the manor house as follows:

“The interior of the residence of the last Count de Barral captures the very essence of the luxury that flourished under Louis XV during the last years of Pompadour. Rich gilding covered every surface and, at each turn, one discovered yet another boudoir.”

This good taste likewise struck Alexandre Delisle, who wrote:

“The Chateau of Allevard is large and commodious. It is surprising to find, in this out-of-the-way place, a residence furnished in such taste and decorated with numerous paintings, many by recognized masters. The gardens were shaped initially by the natural contours of the land which rose up around the area in inaccessible bluffs. The subsequent artistic planting at their base produced a picturesque setting of the highest imaginable enchantment. Down a pathway, one encountered a kiosk some sixty rods south of the chateau. It sits on a precipice above the Breda which forms several sites (‘moments,’ as the landscape architects like to say) of outstanding beauty throughout the garden. In the surrounding forests, M. de Barral had caused to be built a series of benches for the benefit of those whose curiosity about this dramatic setting had led them onto the steep pathways.”

Such observations are puzzling, as they portray Paulin de Barral as a contemplative man, responsive to the beauties of the world and of art, a man whose personal library encompassed “everything of importance to the cultivated man of the Enlightenment” (Salamand, p. 107). Can this be the same man described as possessing a stormy, disrespectful temperament? the same man whose hand required washing each time a physician wished to take his pulse, so deplorable was his personal hygiene? Such a list of charges seems, by these lights, questionable at best.

If we remove, here, the ghost of the “fetish” and the Freudian interpretations that dog this line of analysis, then new doors and dimensions of our story can be opened. It is not impossible that what really obsessed Paulin de Barral was a more subtle work of aesthetic practice, a deeper dive into “aesthesis” — which is to say, in particular, a celebration of the power of the senses, a program decried and misunderstood by his time (and, to some extent, even by our own).

Barral’s secrets will unfortunately never be completely revealed, and our principle source of information about his life is the memoir written by his wife which can hardly be considered objective. On the other hand, we do know that Barral regularly kept a notebook-diary that might have revealed such secrets. However, it is unlikely ever to be found, or so his Barral’s biographer, Georges Salamand, who refers to this missing document as the “Holy Grail” of his research:

“In 1942, the then owners of the ironworks, the Directorate of Mines of the Marine d’Homecourt, were required by the Vichy government to turn over the archives of Paulin de Barral. They were censored so badly that in 1977 I noted some overlooked items, which caused me to continue my pursuits up to this very day. But the journal of Paulin de Barral, mentioned in 1784, has disappeared forever. I am convinced that it contained ‘THE key’ to Laclos’s Dangerous Liaisons.”

Those familiar with the practices and history of the Order of the Third Bird will not find tangible proof here that Paulin de Barral belonged to this organization, evidence for the long existence of which always requires considerable effort to unearth. One additional consideration, however, may well shape our final conclusion: The Chateau Barral has recently been sold off in shares to various purchasers. One such buyer, upon undertaking a renovation of the newly acquired apartment, made a surprising discovery. When these new owners set about demolishing a closet, the family (whose name I will withhold because they wish to remain anonymous to avoid being set upon by archive-fetishists) admitted to me that they had discovered a small chest decorated with a carved wooden bird, and containing a pair of particularly finely made shoes.

During our conversation, my source made mention of this find, before revealing inadvertently that a sheaf of papers, also found in the box, contained some brief handwritten notes. These writings have not been turned over to me, but rather lent for just enough time to copy some of the entries — although not without considerable difficulty, given the nature of the script in question. These texts are still under study at this time by our researchers and archivists, searching through what has come to be called “The W-Cache” for additional clues about the activities of this mysterious and attentionally-extravagant nobleman.

What we can say at this juncture, while we await the production of facsimiles permitting the publication of the documents, is that these notes, in their readable sections, describe the esthetic relationship that the Count maintained with each item in his collection. These observations are presented in four categories, marked by designated symbols, but not titled in words. Included in these groupings are brief letters of invitation to the Chateau for the purpose of “group contemplative practices,” or for a “meeting of the greatest esthetes of the region.” Such letters cannot possibly be taken as examples of invitations to engage in “debauchery” (as they are by Anne Giraudeau in a recent scholarly article), but rather, as those initiates of the Order of the Third Bird will recognize, these invitations almost certainly reflect familiar calls to the practice of sustained attention that has been the hallmark of the Avis Tertia throughout the ages.